Stories of Puget Sound Recovery:

Trekking the Backroads Counting Culverts for Salmon

Members of the culvert mapping project from left to right: Lara Kawal, Jim McCullough, Coleman Byrnes. Photo Credit: Tim Rue

“The Sound is my backyard, the Sound is my dinner table, the Sound is my heart. We call it the Salish Sea and it is everything, it is life. It’s traditional, it’s hopeful—my being here is because of the Salish Sea, so it means everything to me. We were created as salmon people in the Elwha River, so it’s very, very important.” – Russ Hepfer

For Russ Hepfer, Vice-Chairman of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribal Council, tribal culture and salmon are inseparable. But these days, salmon are hard to come by, says Hepfer, who has seen steep declines in fish runs throughout his lifetime. The sockeye populations the Elwha used to rely on have largely disappeared, and king salmon are now protected species. “We’ve lost all our fisheries,” he says. “We’ve been forced to fish for chum [salmon] in the Hood Canal.” What’s keeping the salmon from coming back? “In my opinion, it’s habitat,” says Russ. “We’re destroying it faster than we can restore it.”

One cause of habitat destruction: fish-blocking culverts, which are structures that allow water to flow under a road or similar obstacle but too often prevent fish from migrating to their native habitat. Culverts block fish from reaching their spawning grounds in many ways. They can become blocked with debris or have too little water flowing through them for fish to swim through, they can be too steep for fish to navigate, or water flowing through the culverts can be moving too quickly for fish to swim upstream.

“Culverts are designed to keep water moving, they’re not designed to accommodate fish. That’s the biggest problem,” says Russ.

The Start of a Solution

Cheryl Baumann manages the North Olympic Peninsula Lead Entity for Salmon, a coalition that brings together partners to coordinate and advance local salmon recovery efforts. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe participates in the coalition, along with the Makah and Jamestown S’Klallam Tribes, Clallam County, the cities of Port Angeles and Sequim, citizens and local non-profit environmental groups. The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe’s Habitat Restoration Manager Mike McHenry advocated for a mapped inventory of culverts that negatively impact salmon by blocking their prime rearing habitat, says Cheryl. “Once we have that, we can analyze the data and figure out a plan to remove or fix them so salmon can get through to healthy places to spawn and rear their young.”

The Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe partnered with the Lead Entity to propose a project for inclusion in the Action Agenda for Puget Sound that would map out culverts along County-owned roads. The Action Agenda for Puget Sound is the comprehensive recovery plan that incorporates regional strategies and specific actions to restore and protect Puget Sound.

With Lead Entity support, Cheryl helped secure funding, which she pieced together from state and federal sources. The Strait Ecosystem Recovery Network selected the project to receive a grant from the National Estuary Program. Clallam County Road Department donated use of county vehicles for transportation to find the culverts. Cheryl then tapped the Lead Entity’s Habitat Restoration Planner Eric Carlsen to lead the fieldwork with help from the Clallam County Streamkeepers, a citizen science organization with volunteers who collect and monitor data on stream health.

Carlsen conducted an initial training for five Streamkeeper volunteers interested in the mapping project. Two volunteers who took particular interest, Coleman Byrnes and Jim McCullough, completed most of the investigation, working alongside Eric. What inspired the two to dedicate themselves to the project? “I used to see an abundance of marine life, but not so much now, and I’d like to see that reversed,” says Coleman. “I hadn’t worked with culverts before but wanted to because it’s an important part of salmon recovery. I saw it as a way to broaden my knowledge about hydrology and fish. And I love walking.”

That love of walking was essential to the culvert mapping project. As Eric notes, “we walked all the roads. You can’t find the pipes if you’re just driving.” The trio drove hundreds of miles along Clallam County roads, frequently stopping to walk the shoulder, looking for signs of culverts.

It was slow going. On a good day they could get to 20 sites. Hard rain slowed efforts significantly, and winter brought an abundance of overcast days with light rain. On days with the heaviest rain, water flowing out of culverts was sometimes chest-deep, preventing the mappers from even feeling the pipes.

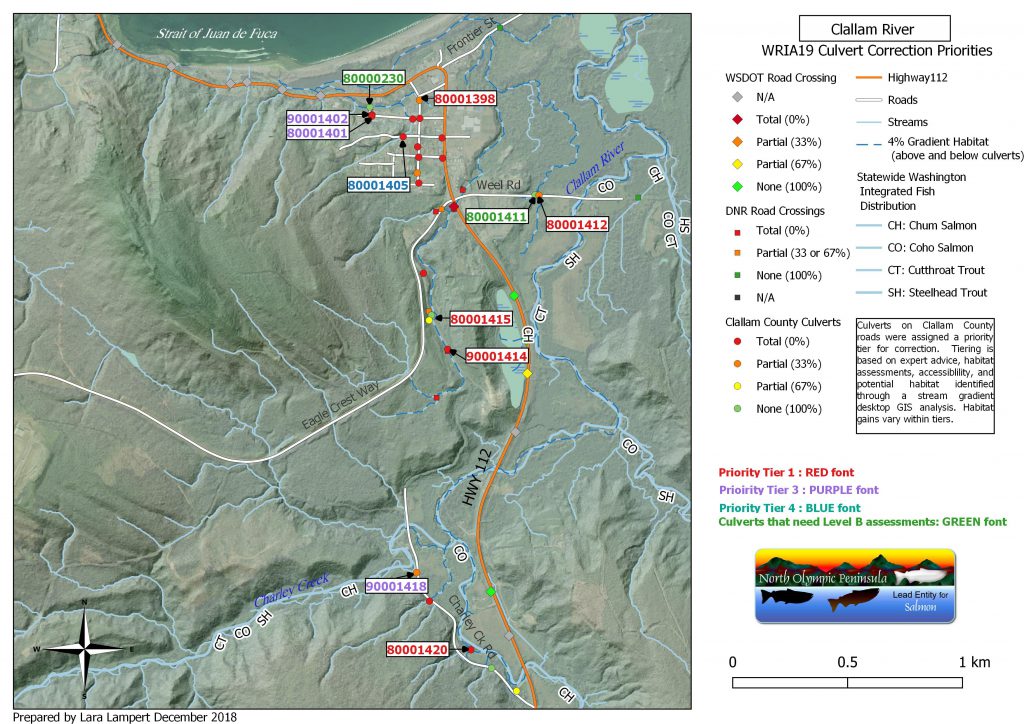

Once the team found a culvert, the real work began. They collected a long list of data, from the shape and dimensions of the pipe, to what it was made of, to the depth of water inside and in plunge pools at the exits. After creating a site ID for each culvert, they compiled the information and entered it into a GIS mapping system.

They began their work in August 2012 working part time; Eric estimates that they searched for culverts an average of four days per month, every month, until June 2018—nearly 300 days. In that time, they gathered GPS coordinates and data for nearly 2,800 culverts on Clallam County-owned roads, walking over 1,000 miles in the process.

The field work data collection was just the beginning. Next, the County hired Lara Kawal to complete in-depth geospatial mapping and data analysis. Technical support and prioritization efforts were assisted by the Makah and Elwha Tribes, and representatives from Clallam County Community Development and Roads, Lead Entity Technical Team Members and the North Olympic Salmon Coalition. Partners looked at percent passability, gradient, channel width, wetlands, and other barriers above and below to prioritize which culverts to fix first.

In addition to providing data to improve the habitat upon which salmon and other species depend, this project demonstrates the deep connection that people who live here have to the Sound. Sound Stewardship—one of the Puget Sound Vital Signs that measure ecosystem health and progress toward Puget Sound recovery goals—is a measure of the extent to which Puget Sound residents engage in environmental stewardship activities that they perceive as meaningful to themselves, their community, and the environment. In a 2018 survey, respondents in the Clallam County area reported that they engaged in stewardship activities, on average, anywhere from once a week to once a month, which is more frequently than the average resident in the region.

From Mapping to Removal

“I totally want this work to lead to on-the-ground construction to fix fish barriers,” says Cheryl. “This inventory is a living document—it will guide future restoration efforts but will require regular updating to remain current.” The mapping project is just the beginning, because the culverts that Eric, Jim, and Coleman identified were only those on Clallam County roads. Hundreds more likely exist on private roads that we not part of this project.

Nonetheless, completion of the project represents a big step forward for salmon recovery. This effort has already helped the Lead Entity to secure funding from Washington’s Brian Abbott Fish Barrier Removal Board for correcting barrier culverts in the Hoko Watershed, which supports the largest natural coho salmon and winter steelhead populations on the North Olympic Peninsula. Earlier this summer, the North Olympic Salmon Coalition, one of the state’s 14 regional fisheries enhancement groups, completed construction of a bridge which replaced a barrier culvert in the Hoko. It was the first culvert replacement completed in Washington with funds from the Brian Abbot Fish Barrier Removal Board.

“Potentially several hundred miles of stream could be opened up by repairing culverts,” Coleman says. “We’re now investigating which culverts to prioritize and are looking to reconnect habitat to fish around the Puget Sound.” Though this particular mapping effort is over for now, further work is needed in other parts of the North Olympic Peninsula, providing ample opportunities for committed volunteers – as Coleman states: “you have to get out and look for them, you can’t sit around in an office and do it. Some of these are hard to find. It’s an on-the-ground activity.”

There’s still a lot of work to be done to ensure that salmon habitat is restored in Clallam County, but Russ Hepfer remains optimistic: “If you build it, fish will come.”

More about culverts in Washington

In May 2017, the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed that the state must accelerate work to remove, replace, and repair fish passage blocking culverts. This decision was subsequently affirmed by the Supreme Court of the United States in June 2018. The state increased funding for fish barrier removal projects in Puget Sound from $54 million in the 2015-17 biennium to $71 million in the 2017-19 biennium. For the current 2019-21 biennium, Washington state has budgeted $275 million for culvert removal.

Though the state of Washington is required to remove fish passage barriers on state owned lands, many barriers also exist on private, local, and federal lands. Effectively restoring salmon access is only likely to occur if other downstream and upstream barriers on the same rivers and streams are also removed on non-state lands. This is recognized in state law, which requires the Departments of Fish and Wildlife and Transportation to work with local governments and other entities to coordinate investments and correct multiple fish barriers in whole streams rather than through individual projects in isolation. A full inventory of all multi-jurisdictional barriers in a watershed enables prioritizations of barriers for removal to maximize the benefit of newly restored fish passage.

Vital Sign Connections

Chinook and other salmon species depend on access to stream habitat to lay their eggs and to support young salmon as they feed and grow. Mapping culverts in Clallam County helps prioritize which culverts should be removed first to provide the most habitat for salmon.

Cultural wellbeing depends on a range of cultural practices linked to the natural environment, including recreational, civic, and social activities, as well as tribal cultural practices related to natural resources. Salmon are a cultural icon of the Pacific Northwest and will benefit from the removal of culverts to increase their natural habitat in Clallam County.

Puget Sound residents engage in environmental stewardship activities that they perceive as meaningful to themselves, their community, and the environment. Stewardship of natural resources is demonstrated by volunteers featured in this story to support the recovery of salmon populations and the habitat they need.

Action Agenda Connections

The Action Agenda—the Puget Sound Partnership’s regional plan for protecting and recovering Puget Sound—prioritizes salmon habitat restoration projects, including the removal of culverts and other fish passage barriers that block or impede salmon access to their spawning and rearing grounds.

The project featured above was included as a priority Near Term Action (NTA) in the 2016-2018 Action Agenda to identify and map culverts for removal. The Action Agenda’s inventory of ongoing activities to protect and recover Puget Sound also includes the following programs that make significant contributions to correct barriers on state, local, and private lands:

- Washington Department of Transportation – Fish Barrier Correction

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife – Brian Abbott Fish Barrier Removal Board

- Washington Department of Natural Resources – Family Forest Fish Passage Program

- Federal funds from the EPA’s National Estuary Program and NOAA’s Pacific Coastal Salmon Recovery Fund.

More Information

Story Links:

NOPLE Clallam County Culvert Inventory

Western Strait fish barrier removal in the Hoko watershed

Department of Fish and Wildlife’s fish passage geo-database inventory